This post features research conducted during an internship for the onwork project, as part of a Bachelor of Philosophy at Macquarie University. The project set out to explore Alasdair MacIntyre’s writings and outline his contributions to the debates on work.

The research covered the following texts:

MacIntyre’s writings:

Dependent Rational Animals (1999)

The Tasks of Philosophy, Volume 1: Selected Essays (2006)

Ethics and Politics, Volume 2: Selected Essays (2006)

MacIntyre’s economics – brief written reply (2011)

‘Replies’, Revue Internationale de Philosophie (2013)

Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity (2016)

Secondary literature:

MacIntyre and Business Ethics (Beabout 2020)

“Moral Education at Work: On the Scope of MacIntyre’s Concept of a Practice” (Sinnicks 2019)

“Utopia Reconsidered: The Modern Firm as Institutional Ideal” (Dobson 2008)

“Goods” (Knight 2008)

Practices, Firms and Varieties of Capitalism (Keat 2008)

“Practices, Governance, and Politics: Applying MacIntyre's Ethics to Business” (Sinnicks 2008)

MacIntyre, managerialism and universities (Stolz 2017)

Worlds of Practice (Higgins 2010)

Under Weber’s Shadow (Breen 2012)

“MacIntyre, Rival Traditions and Education” (Stolz 2016)

“On the Implications of the Practice–Institution Distinction” (Moore 2002)

While the secondary sources revealed a number of fruitful citations and discussions of a MacIntyrian view of work, this post focuses on contributions by MacIntyre himself.

MacIntyre’s strong criticism of modernity, much of which focuses on the pathologies of the economic system and its underpinning ideological tenets, could lead one to believe he is anti-work, or at least that some of his arguments can be enlisted to advocate post-work society. He views modernity as incompatible with moral agency, argues that capital creates an environment in which hard, skilled, and conscientious work will be rewarded by unemployment if it does not generate sufficient profit, claims capitalism creates compartmentalisation because of the various incompatible roles we must inhabit to succeed, opines that business ethics are a waste of time and management in many forms is amoral.

However, while strongly criticising the structures of our current social, political and economic order and how they impact labour, amongst other things, in many respect MacIntyre actually makes a case for work. He only believes that modernity has prevented most people from achieving the goods that work can bring.

MacIntyre’s views can apply to work in at least three different dimensions:

1. Work contributes to our ability to develop our practical reasoning skills

2. A lack of work impoverishes our moral agency

3. Achieving workplace goods is constitutive of achieving individual goods

Each of these areas are discussed further below, but first we must deal with MacIntyre’s key concept of practices.

Practices

According to MacIntyre’s oft-quoted definition, a practice is:

“any coherent form of socially established cooperative activity through which goods internal to that form of activity are realised in the course of trying to achieve those standards of excellence which are appropriate to, and partially definitive of, that form of activity” (After Virtue 2007, p. 187).

Work, both paid and unpaid, can be, but is not necessarily, a practice for MacIntyre.

As MacIntyre notes, the proper pursuit of a practice has

“the result that human powers to achieve excellence, and human conceptions of the ends and goods involved, are systematically extended” (After Virtue, 2007, p. 187).

Consequently, when it does not provide the opportunities for the worker to access the internal goods inherent to that work, or is not morally educative, it is not count as a practice.

Throughout life, we are exposed to a variety of practices through which we learn to recognise the goods internal to each, which can be only be achieved through the exercise of virtues and skills. These internal goods are not the telos of the practice, rather they are

“the excellence specific to those particular types of practice which individuals achieve or move towards in the course of pursuing particular goals or particular occasions.” (Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity, p. 38).

Given that modernity recognises internal goods only for the contribution they make to attaining external goods (money, power, status etc.), institutions cause the subordination of internal goods to the pursuit of external goods, and thus corrupt their own practices. This subordination is sinister because, while external goods can be attained with little ability in a practice, internal goods represent a participant’s true capabilities and ends. Further, because external goods have become a leading measure of success, participants must treat others as means to their ends (of obtaining external goods).

This concept of a practice is key to understanding MacIntyre’s views on work, as he does not frequently discuss “work” or “labour” directly. Instead, MacIntyre centres his thoughts on practices, and the contribution they can make to human flourishing.

In what follows, each dimension of MacIntyre’s thoughts on work are explored with reference to pertinent citations in the sources reviewed.

1. Work contributes to our ability to develop our practical reasoning skills

For MacIntyre, a practice is instrumental in helping us to test our practical reasoning, and protecting us from faulty reasoning.

In Dependant Rational Animals (1999), MacIntyre discusses the importance of interacting with other people for our practical reasoning, highlighting that our reasoning may go astray because of intellectual or moral error, with intellectual errors often rooted in moral errors. MacIntyre suggests that the best protection against these errors are “friendship and collegiality”. When discussing specific practices, MacIntyre notes that we must rely on our expert coworkers to

“make us aware both of our particular mistakes in this or that practical activity and of the sources of those mistakes in our failures in respect of virtues and skills... “ (p. 58)

MacIntyre expanded on this idea in Ethics and Politics (2006), noting that, because our intellectual errors are often based in moral errors, we

“need therefore to have tested our capacity for moral deliberation and judgment in this and that type of situation by subjecting our arguments and judgments systematically to the critical scrutiny of reliable others, of co-workers, family, friends.” (p. 191)

In Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity (2016) MacIntyre again discusses the importance of deliberation with others in an effort to mitigate our fallibility and liability to error. It is important who we deliberate with and how we do so, and while noting that the manner of deliberation will vary greatly depending on where it takes place, MacIntyre specifically notes that, at various times in our lives, deliberation in the workplace will be

“of crucial importance both for the projects of home, school, and workplace and for the individuals engaged in those projects” (pp.192-3).

Hence, work for MacIntyre provides one of the necessary milieus for developing and testing our practical reasoning skills because it is one of the main environments in which we interact with others. This is not to say we should view all of our colleagues as omniscient beings who have all the correct answers and know better than we do what we ought to do in a particular situation; it is simply that the workplace provides us with the opportunity to deliberate with others and, in deliberating thus, we are more likely to be able to identify our own, and others’, intellectual or moral errors.

2. A lack of work impoverishes our moral agency

MacIntyre’s thoughts on the impact of work on moral agency are key to his chapter ‘Social Structures and their Threats to Moral Agency’ in Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity. For MacIntyre, work (when it counts as a genuine practice) provides opportunities to understand what it is to be a rational agent, to “begin in moral and political enquiry”, and enrich our moral experience (p.58).

MacIntyre highlights that our social setting and the roles we hold contribute to our development as moral agents. The nature of being a moral agent includes responsibility; we are responsible for our decisions and actions. Regardless of whether we accept the breadth and implications of our moral responsibility, as persons (those with the capacity for moral agency) moral agents need to be accountable – we need to be able to provide reasons for making the choices we do and the people we are. Our socially assigned roles are accompanied by particular accountabilities that we owe to

“particular others, to whom, if [we] fail in [our] responsibilities, [we] owe an account” of our failure. The responsibility necessary for moral agency would be “empty” without this accountability (Ethics and Politics p. 191-2).

The link to work is in our social roles and relationships – without these we would be left with “a seriously diminished type of agency, one unable to transcend the limitations imposed by its own social and cultural order”. Hence, MacIntyre concludes “[m]oral agency thus does seem to require a particular kind of social setting” (Ethics and Politics pp. 191-2).

Perhaps even more relevantly for work, MacIntyre goes on to note that

“[t]here must therefore be a place in any social order in which the exercise of the powers of moral agency is to be a real possibility for milieus in which reflective critical questioning of standards hitherto taken for granted takes place. These too must be milieus of everyday practice [later, p. 193, expanded to include “certain kinds of workplace” amongst other things] in which the established standards are, when it is appropriate, put to the question and not just in an abstract and general way” (Ethics and Politics, p. 192)

The relationships we have in the workplace, with managers, peers, subordinates, stakeholders, board members, and myriad other individuals, entail responsibilities specific to those relationships. We are accountable to those individuals, although in different ways, for our decisions and actions and the workplace is thus an environment in which the responsibility necessary for moral agency can be both developed and tested. Beyond this, the workplace provides opportunities for us to develop and practise our reflective critical questioning of standards – MacIntyre is encouraging workers to thoroughly reflect on their work and workplace and, “when it is appropriate” to question why things are done in certain ways. This skill is one that, one might argue, is severely lacking in our everyday lives, and by providing a “practice space”, the workplace is essential for our individual flourishing.

3. Achieving workplace goods is constitutive of achieving individual goods

The strongest case for work in the sources reviewed is MacIntyre’s view that individuals cannot achieve their own goods without also achieving the goods of the workplace, family, and community. This idea is explored in some depth in Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity.

MacIntyre suggests that it is only through the achievement of “those common goods that we share as family members, as collaborators in the workplace, as participants in a variety of local groups and societies, and as fellow citizens” that we can achieve our own individual goods. Workplaces can be a means to achieving our own preferences (Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity pp. 106-7).

Without common goods, the individual is “abstracted” (Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity pp. 106-7) from both their social relationships and from the norms of justice that inform those relationships, and is unable to flourish. The workplace provides an environment in which the common goods served by productive work can be achieved, and the “ethos” of the workplace is “characteristically and generally” one of the marks of a good human life (Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity p. 118).

There is a strong connection between the spheres we inhabit in life – as MacIntyre notes, the goods of the family are impacted by the workplace; for instance, when one or both caregivers are unemployed, underpaid, underemployed, work too long hours or are unable to afford decent housing. Children in these households are often negatively impacted when it comes to education (among other things) and thus the goods of the school are affected by the home and the workplace. And it becomes a vicious circle, because a “flourishing workplace” needs workers with the relevant skills and the ability to improvise, but these workers can generally

“learn what they need to learn in the workplace, only if they have been first well educated at home and school, so the goods of the workplace become vulnerable to the circumstances of the home and school” (Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity p. 176).

In a lengthy description about the approaches towards workforce involvement of a Japanese automobile manufacturer and a British TV production company, MacIntyre contrasts a workplace in which workers can pursue ends and standards of excellence that they have identified themselvesas worthwhile, with a workplace in which the ends and standards have been determined, and imposed upon workers, by managers and administrators. MacIntyre argues that in the latter situation, the workers are treated as means to the ends of the management, whereas in the former, even though their labor may still be still exploited, the workers are treated as “agents with rational and aesthetic powers” (Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity pp. 130-2).

Further, for MacInytre, activities associated with the former situation enable individuals to both determine and transform their desires, and to draw distinctions between objects of desire they have good reason to pursue and objects that will not aid in the achievement of excellence. In contrast, in the latter situation, in which workers are treated as means to the ends of another, activities are means to the individual worker’s ends outside of work – most likely a wage that “may make life outside work...more satisfying”; the activities are not inherently worthwhile in themselves (Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity 131-2).

Over five pages in Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity, MacIntyre discusses local communities, focusing in some detail on the fishing community of Thorupstrand in Denmark. As with the example of a Japanese car manufacturer and a British television production company, MacIntyre contrasts the nature of work in a community such as Thorupstrand with that of a large corporation engaged in deep sea fishing. Work in such an organisation is directed to serving the ends of the corporation, shareholders, managers etc. in return for earning a living. Importantly, in this situation, MacIntyre highlights that “there is only or principally a financial connection between your work and the ends that you have as member of a family or household or as member of a local community.” In other words, the connection between the various spheres of life is solely monetary, which MacIntyre argues is a deficient way of living, as compartmentalisation between the spheres of life prevents flourishing (Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity, p.179).

In the fishing community of Thorupstrand, every member of a crew was a partner in a joint enterprise, costs and earnings were shared. Because of this, individuals were cognisant of the three related common goods: of family, crew, and local community. Individuals were also aware that their own individual ends were achieved

“in and through cooperating to achieve those common goods. What they share...is that their work is not a means to an external end but is constitutive of a way of life, the sustaining of which is itself an end.” (Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity, p.179)

Earlier in his work, MacIntyre draws a direct link between Aquinas and his view that common goods are necessary for individual goods. In Ethics and Politics, a collection of essays written between 1985 and 1999, and published in 2006, MacIntyre discusses Aquinas’s principles of natural law and his view that good ought to be pursued and evil avoided. For human beings, those goods are the good of our physical nature, thof our animal nature, and the goods that “belong to our nature as rational animals”, the goods of knowledge and social life. MacIntyre notes that there are a number of precepts that are directed to achieving “shared human good” or forbidding that which endangers those common goods, such as “never take an innocent life”. The fact that these are precepts of reason means that to violate them knowingly would mean an individual asserting “While it is good and best to do X, I shall instead do Y.” MacIntyre contends that the common goods these precepts are directed toward are

“indeed goods for each of us, qua member of this family or that household, qua participant in the life of the particular workplace or that particular political community. And they are therefore goods that we can achieve only in the company of a variety of others, including not only those others with whom we share the life of a family and household or the life of a workplace or a political community, but also strangers with whom we interact in less structured ways.” (Ethics and Politics pp. 64-5).

By recognising work as essential to the achievement of individual and common goods, small-scale and local communities represent an environment in which

“social relationships are informed by a shared allegiance to the goods internal to communal practices, so that the uses of power and wealth are subordinated to the achievement of those goods, make possible a form of life in which participants pursue their own goods rationally and critically, rather than having continually to struggle, with greater or lesser success, against being reduced to the status of instruments of this or that type of capital formation.” (Ethics and Politics, p. 156)

In 2013, MacIntyre authored a short series of ‘Replies’, in the Revue Internationale de Philosophie, in which he discussed virtues in the context of practices, and stated explicitly that

“practices remain and cannot but remain central to human life and so the importance of the virtues is recurrently rediscovered” (Replies, pp. 216-7).

Final thoughts

MacIntyre specifically tells us that work is a good in Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity:

The first is a matter of identifying a set of goods whose contribution to a good life, whatever one’s culture or social order, it would be difficult to deny. They are at least eightfold, beginning with good health and a standard of living – food, clothing, shelter – that frees one from destitution. Add to these good family relationships, sufficient education to make good use of opportunities to develop one’s powers, work that is productive and rewarding, and good friends. Add further time beyond one’s work for activities good in themselves, athletic, aesthetic, intellectual, and the ability of a rational agent to order one’s life and to identify and learn from one’s mistakes. (Ethics in the Conflicts of Modernity p.222)

MacIntyre is absolutely critical of the structures of our modern way of life that cause us to work in roles that may be exploitative, or for which we have to hold very different values than we do in the rest of our lives. However, MacIntyre is clear that when work enables us to develop our practical reasoning skills, and exercise and challenge our moral agency, it becomes a practice, and when that occurs, work is “central” to human life and constitutive of human flourishing.

Lindsay Roberts

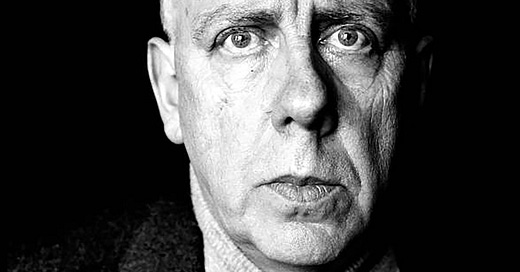

Picture:

Levan Ramishvili, Alasdair MacIntyre, London, March 24, 1992.