Bullshit et al.

The repository now contains almost 4500 entries. Many of the recent entries focus on workplace automation, particularly on automation by way of AI and “intelligent machines”. We are currently using these resources to write a critical review article on the scholarship on artificial intelligence in the workplace. We also recently added many important references on work and well-being, often discussed in terms of “meaningful work” or indeed in terms of the opposite, “bullshit jobs”. There are now over 160 entries on “meaningful work” alone, with many more on related themes.

Meaningful work is a broad topic, and the concept itself is highly contested. After all, work always has some meaning to the worker, possibly a negative one. Breen (2019) makes an important clarification about the distinction between meaning and meaningfullness. Work might be viewed merely as a source of income, or as a burden, or as source of joy, or as a stressor. Whatever it is, work will nearly always mean something to the worker. But, merely meaning something isn’t the same as work being “meaningful”.

There are many scholarly accounts of what makes work meaningful. An important collection is the 2019 Oxford Handbook of Meaningful Work. Uncovering the meaning and the conditions for meaningful work is not, however, exclusively a recent concern. Adina Schwartz’s 1982 article, one of the foundational texts in this area, argues that meaningful work requires that workers are respected as “autonomous agents”. More specifically, it is found where workers are respected by being allowed to “decide how to perform their particular job”. The search for meaningful work in this case is led by an ideal of autonomy articulated in moral and political terms, as “meaning” here is one which industrial society overlooks or even overtly seeks to prevent. As Schwartz writes, “instead of being hired to achieve certain goals and left to select and pursue adequate means, workers are employed to perform precisely specified actions.” (p.634).

Autonomy remains a key concept in recent literature on “meaningful work” and is often associated with discussions of the subjective value of work for workers. Discussion of worker autonomy is taken up from a variety of disciplinary angles, in workplace psychology, organisation and management studies, as well as political philosophy, notably in relation to workplace democracy as well as republican and socialist theories of work. In a number of recent accounts, this focus on agency has been combined with a consideration of the sources of meaning that can be found outside of work. A leading example is Bailey and Madden, who argue that what makes work meaningful is “its connection to something beyond the immediate tasks and roles, to something that is deemed, voluntarily, to be worthwhile in terms of overall life purpose.” (2019, 2) In their earlier 2016 work, the authors gave a clear delineation of this connection:

Finding your work meaningful is an experience that reaches beyond the workplace and into the realms of the individual’s wider personal life. It can be a very profound, moving and even uncomfortable experience. It arises rarely and often in unexpected ways; it gives people pause for thought not just concerning work, but what life itself is all about. In experiencing our work as meaningful, we cease to be workers or employees and become human beings, reaching out in a bond of common humanity to others. (p.14)

However, if a condition of meaningful work is that it really matters in the world, problems arise if we don’t believe that our work in fact does have an impact. This is a problem because this lack of belief would be precisely the conditions for meaningless work.

A related concern has emerged in recent years, captured in a concept which has received significant traction both in the academic and public eye, namely David Graeber’s idea that a lot of contemporary work involves “bullshit jobs”. A “bullshit job” is a job that is so obviously pointless that the worker themselves believes it shouldn’t exist. In the simplest terms, a bullshit job is a job that doesn’t achieve anything productive to anyone. A number of scholars have taken up the concept and fine-tuned it to apply to different areas of contemporary work, for instance Spicer (2017) whose concept of “business bullshit” relates to pointless workplace jargon, or empty “management speak”. Graeber links the spread of pointless work to an idiosyncratic feature of contemporary capitalism, which destroys productive jobs through automation, yet insists on maintaining the necessity to work for all but a few: “It’s as if someone were out there making up pointless jobs just for the sake of keeping us all working.” (2013. p.2) As he writes:

productive jobs have, just as predicted, been largely automated away […]. But rather than allowing a massive reduction of working hours to free the world’s population to pursue their own projects, pleasures, visions, and ideas, we have seen the ballooning of not even so much of the ‘service’ sector as of the administrative sector, up to and including the creation of whole new industries like financial services or telemarketing, or the unprecedented expansion of sectors like corporate law, academic and health administration, human resources, and public relations. And these numbers do not even reflect on all those people whose job is to provide administrative, technical, or security support for these industries, or for that matter the whole host of ancillary industries (dog-washers, all-night pizza delivery) that only exist because everyone else is spending so much of their time working in all the other ones. These are what I propose to call ‘bullshit jobs’. (p.2)

Graeber is referencing, as many scholars do currently in the post-work literature, a famous claim by Keynes, who in his 1930 Economic Possibilities for our Grandchildren wrote that productivity increases over the next 100 years would lead to a state of “economic bliss” whereby the “economic problem” – which is that people need to work to pay for their basic needs – is finally overcome by technology. For Graeber, the replacement of human by machine work in many productive sectors has perversely led, not to a lowering of working hours, but rather to the displacement of workers into newly created non-productive, bullshit, jobs. Entire industries, he argues controversially– financial services and human resources for example – have been created to soak up this displacement and are largely (in many cases entirely) comprised of pointless work.

Graeber’s provocative thesis is important for pointing to the consequences of meaninglessness in work. There really is a “profound psychological violence” (p.5) in people having to engage in pointless work.

The knowledge that the tasks we engage in lack the value we would want to ascribe to our work causes harm to us, and Graeber is not alone in highlighting this. There have been many empirical studies on this aspect of meaningful work. Dur and Lent (2019) for instance conducted a study on 100,000 workers from 47 countries and found that an overwhelming number of workers do care about their job being “socially useful” and indeed that they suffer when they don’t believe that their job actually does provide that utility.

However, many scholars are skeptical about the scenario put forward by Graeber of contemporary capitalism wilfully maintaining large part of the workforce in useless and meaningless work for the sake of it. Dur and Lent, who did take Graeber’s hypothesis seriously, found that only 8% of workers really do perceive their job to be “socially useless” substantially undermining Graeber’s claims of up to 60% of workers. Similarly, Soffia et al. in a new study in Work, Employment and Society provide substantial empirical evidence against the claim of a vast spread of bullshit jobs. Testing five of Graeber’s core hypotheses they found that “the portion of employees describing their jobs as useless is low and declining”, concluding that “BS jobs are a rare phenomenon.” As they write:

Not only do our findings offer no support to this theory, they are often the exact opposite of what Graeber predicts. In particular, the proportion of workers who believe their paid work is not useful is declining rather than growing rapidly, and workers in professions connected to finance and with university degrees are less likely to feel their work is useless than many manual workers. (p.20)

This research confirms that workers’ own belief about the importance of their work is intrinsically tied up with their wellbeing. In place of Graeber’s theory, the authors present an alternative explanation:

Graeber believes that when individuals report their jobs as being useless, this is an accurate appraisal by the individual of their job’s social value. This, view of paid work as constraining essential human agency is striking in its resemblance to alienation, yet this concept is absent from Graeber’s account. Similarly, Marx argued that labour under capitalism is inherently alienating as it blocks individuals’ essential need for self-realisation. However, for Marx this was not the result of individuals being engaged in activity that was of no social value but rather because capitalist social relations frustrate the free development of human abilities in spontaneous activity. (p.6)

This substitution of ‘alienation’ for ‘bullshit jobs’ allows us to take the harms caused to workers seriously, but it allows us to do so without the need to cast a dubious eye over entire industries, cataloguing millions of workers as labouring ‘pointlessly’. However, even though many workers can find self-realisation in their work – regardless of their industry or job title – as Schwartz warned in 1982, workers in industrial societies like ours are not hired because of their ability to find meaning or self-realisation in their work. Work under capitalism can be meaningful, can supply value and support the agency of workers, but these cases might well be the exceptions to the norm.

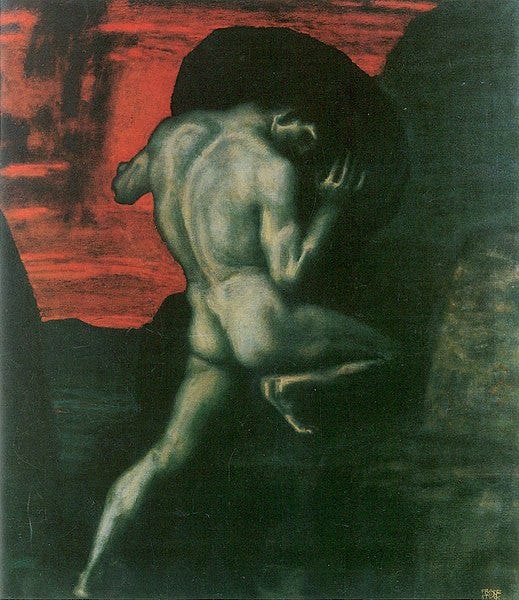

Image

von Stuck, Franz. Sisyphus. 1920, Germany. Public Domain.