In recent weeks, our efforts have focused on the theme of “Deutsche Arbeit”. The term could point simply to the long tradition of German writings on work, all the way to Luther, but here it refers more specifically to a key motto in German politics and culture in the 1930s. This was a time when work was indeed pronounced to be central to individual and social life. But this pronouncement was made in the name of a rabidly xenophobic, totalitarian, and as it soon turned out, genocidal ideology. For debates on work, this is a particularly significant case. Does the centrality of work in Nazi ideology and Nazi politics represent more than just one (particularly sinister) empirical case against work? Could it be that this historical example in fact reveals deep traits about modern work as such?

Studying this theme requires references to both modern German history and modern German philosophy.

On the history side, research draws on well-established historiography of National-Socialism to focus more specifically on the place of work in the movement’s ideology and politics. Researchers trace conceptual elements dating back to Luther, which became amalgamated and mixed with racist and anti-Semitic tropes to produce the highly destructive conception of work that was operationalised in Nazi policies.

On the philosophy side, the authors that are prominently discussed are two of the most influential disciples of Nietzsche in the 20th century, namely Martin Heidegger and one, whom Heidegger called “the only genuine follower of Nietzsche”, namely Ernst Jünger.

A key document in this field is Werner Hamacher’s text “Working through Working” (“Arbeiten durcharbeiten”). In this article, the German philosopher compared the conceptions of work to be found in Jünger and Heidegger with statements by Adolf Hitler in some of his major speeches. Hamacher’s leading question is precisely whether the fascist conception of work in fact does not unveil fascist elements in modern work itself:

What does “work” mean in fascist ideology and, insofar as this ideology is an integral moment of the fascist system, what does “work” mean as a fascist institution? (“Working through working”, 26)

This is part one of two on the theme of Deutsche Arbeit. We won’t try in this newsletter to answer these complex questions, or indeed take a stance on Hamacher’s conclusions regarding the inherent fascism of modern work. This first post only provides a brief update on entries related to Ernst Jünger. The next post will update entries on Heidegger.

Ernst Jünger

We have now entered 51 citations from Jünger’s Der Arbeiter (The Worker). The book published in 1932 consecrated Jünger as one of the intellectual leaders of the nationalist, right-wing revolutionary movement. After the war, Jünger became one of the most celebrated authors of the German canon, but for his travel diaries, his novels and meditations, not for his 1932 treatise. Beyond historical interest, why return to this old book?

Jünger’s English translators, as well as a few commentators, believe the book presents a viable, alternative critical theory of globalisation, through his depiction of industrial, capitalistic work and how it has taken over the whole planet. Marcus Paul Bullock even reads the book as offering an “alternative utopia” to more traditional “left-wing” or “liberal” ones:

“The meaning of Der Arbeiter begins to emerge […] when considered as a utopian text constructed in that spirit of resistance one should look for in all utopian writing. Its significance lies in the effort to establish an alternative conception of freedom and an alternative to bourgeois utopianism.” (Flight Forward, 453)

The book’s sub-title is “Domination and Form”, “Herrschaft und Gestalt”. Contemporary domination, the book argues, is exercised by a new “type” (Typus), a kind of metaphysical principle that broke through as the old European order collapsed under the overwhelming brutality of the First World War. This type is the Typus of the Worker, a new mode of life and organisation which mobilises all the powers of technology to stamp its will onto all dimensions of reality, to “shape” and give it “form”:

“The process in which a new form, the form of the worker, comes to expression in a distinctive humanity, manifests itself in terms of mastery over the world as the arrival of a new principle which shall be categorized as work. Through this principle the forms of confrontation of our time take their only possible shape: it undergirds the platform on which anyone can meaningfully engage with any other, if we think to engage with others at all. In this lies the arsenal of means and methods through whose superior handling we will recognise the representatives of an incipient power.” (The Worker, 57)

As this citation shows, the problem with readings that find in the book an accurate anticipation of 20th century modernity or a depiction of an original post-liberal utopia, is that, in it, Jünger explicitly embraces what he sees as the new world-historical principle, and such an embrace in turn leads to some fairly hyperbolic statements, and worse still, entails some highly worrying implications. The following passage is a good example:

Once we have recognized what is needed now, namely assertion and triumph, or –if needs must–even readiness for utter collapse within a thoroughly dangerous world, then we will know which tasks are to take control of every kind of production, from the highest to the simplest. And the more life can be led in cynical, Spartan, Prussian, or Bolshevist way, the better it will be. The established standard is to be found in the way the worker leads his life. It is not a matter of improving his way of living, but of conferring upon it a highest, decisive meaning. (The Worker, 143)

Jünger links the new “type” embodying the time as an expression of the will to power, indeed, as the will to power finally liberated from the shackles of nihilistic European culture and the long, “bourgeois”, 19th century. As the expression of liberated will to power, the “form of the worker” makes possible total “mastery over the world”, Herrschaft, “dominion” over the natural world and over other men. The form of the worker, the principle of the post-nihilistic world, selects a “distinctive humanity” as its agents and “representatives”, who are thereby able to exercise its “incipient power”. As it is situated “beyond good and evil”, the manifestations of this power include the unleashing of technological means, not just for shaping and giving “form”, but just as much for destruction. Or rather, destruction, being an expression of the will to power, must itself be regarded as a kind of “form-giving”. “Total mobilisation” (also the title of a smaller treatise preceding Der Arbeiter) is thus the genuine mode of action of this new principle, in two different senses: first, as “making mobile”, that is, mobilising the energy inherent in all established features and realities of the world; and secondly, in the sense of a total commitment by individuals and collectives to achieve the ends that manifest their will to power:

“Power within the world of work can therefore be nothing other than the representation of the form of the worker. Here lies the legitimation of a new and special will to power. One recognizes this will by the fact that it is the master of its means and weapons of attack, and in the fact that it does not possess a derivative, but a substantial relationship to them.” (The Worker, 49)

Reference to the “weapons of attack” that the liberated figure of the will to power has “a substantial relationship to” confirms that for Jünger it is war, total war, that is the most authentic manifestation of the age:

the age of the worker … is endowed with an elemental relationship to war and is thus able to represent himself militarily by his own means. (The Worker, 107)

Embracing the “form of the worker” thus translates into welcoming aspects of modernity that most would rather condemn than accept: total domination of the human and natural worlds by technique, including human individuality; the possibility of total destruction; in the realm of politics, a move beyond parliamentary democracy to a “work-democracy” that is based on a “state of exception” and issues in a planetary, “absolute”, “work-state”. The “heroic realism” Jünger calls for demands unflinching acceptance of all these features of the new situation. One needs a significant amount of cynicism or philosophical detachment to countenance such a kind of amoral “heroism”.

Moreover, Jünger is not just writing in general terms, from a detached philosophical point of view. The seduction exercised by his book on his contemporaries surely stemmed from the fact that it combined cryptic, philosophical-sounding statements, with direct references to the immediate social, political and cultural context. Next to the denunciations of bourgeois culture, human rights and liberal politics that were common fare in conservative circles during the Weimar Republic, the book is replete with forebodings about what a truly popular, social movement, guided by a “unified caste of leaders”, a “young and ruthless leadership”, will be able to achieve, how it will be able to fulfill the “destiny” of “German freedom”. Passages such as this one give a good idea of the prophetic tone of the book, which captured reactionary imaginations:

“A war veterans movement, a social revolutionary party, an army, transform themselves (in the new circumstances of the “work” character of the world) into a new aristocracy taking possession of the decisive spiritual and technological resources. The difference between such entities and an old-style party is obvious. Here it is a matter of breeding and selection, while the efforts of a traditional party are directed toward the cultivation of masses”. (The Worker, 167)

The connection to the immediate political context seems fairly transparent. The call the book finishes with, “To take part and to serve: that is the task expected of us”, similarly, seems difficult to misunderstand. No wonder that Hamacher read Jünger’s text as “the protofascist manifesto par excellence” (“Working through working”, 32). It is true that Jünger refused to be associated with the Nazis once they came to power but Hamacher reminds us that he had dedicated a presentation copy of Fire and Blood in 1926 to “the national leader Adolf Hitler”. According to Hamacher, Jünger’s distate of the Nazis was more the result of aesthetic high-mindedness than political or moral concerns.

One reason then to still read Der Arbeiter today, is that it is a key document illustrating a view of industrial work in the 1930s that was organically linked to totalitarian tendencies in culture and politics. Whatever the correct interpretation of the book in its relation with Nazi rhetoric, just the totalising statements made in the name of work alert us to what could be a key, significantly pathological dimension of work itself in contemporary times. It could be that Jünger’s hyperboles and amoralistic bravado unwittingly reveal aspects of modern work that critical theorists of modernity have underlined about other aspects of modern society, all based on the urge to dominate and to eliminate otherness.

A more simple reason for returning to Der Arbeiter is Jünger’s influence on Heidegger. Heidegger very rarely engaged with, let alone cited, his contemporaries, but Jünger was an exception. Heidegger discussed Der Arbeiter at length on a number of occasions over the 1932-1942 decade, and again after the war, dedicating entire lecture courses to it. The three manuscripts published in volume 90 of the Gesamtausgabe, covering two decades (1934-1954) give a good idea of the extent of his involvement with Jünger. Michael Zimmerman’s Heidegger’s Confrontation with Modernity is probably still the most thorough study of Jünger’s influence on Heidegger. As we will see in the next post, Heidegger’s writings also contain important lessons for debates on work.

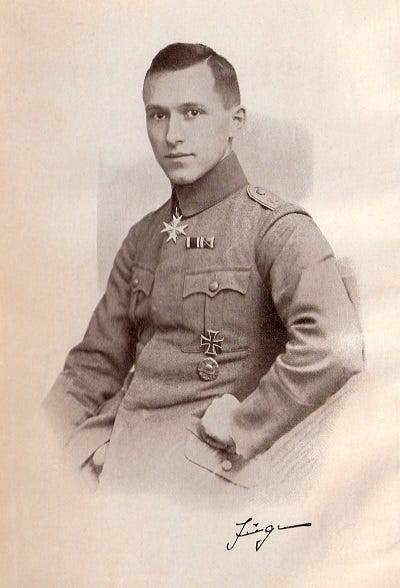

Image

Ernst Jünger (1895-1988). Cover of In Stahlgewittern, Berlin 1922, 3rd edition. Public Domain.

Wow great post!