In recent weeks, our research has focused on Michel Foucault’s contribution to debates on work. Throughout his immense corpus, Foucault never ceased to take work as a central object of his analyses. The History of Madness for instance begins with an alternative account of the new value that work started to take on early in the 17th century, with a shift in the fundamental ethos justifying the condemnations of idleness. These are crucial pages to elaborate an alternative Foucauldian version of the “work ethic” hypothesis. Similarly, in Psychiatric Power, Foucault continues his historical analysis of work into the 18th century, now focusing specifically on “work discipline” and the rising emphasis on the control and management of workers time. The attention and significance Foucault gives to work in his writings is striking and gains yet more weight when we consider his corpus as a whole, over the entire span of his thinking life.

We have collated 84 citations throughout Foucault’s oeuvre in which work is significantly discussed. These citations are organised by publication and complement a collection of a further 133 citations from the secondary literature.

Simply listing the texts included in the repository gives a sense of the importance of work in Foucault’s thinking: the 1961 History of Madness; the 1966 Order of Things; the 1969 Archaeology of Knowledge; the 1972-1973 lectures on "the punitive society” ; the 1973-1974 lectures on "psychiatric power”; the 1974-1975 lectures on “the abnormal”; the lectures “truth and juridical forms” held in Sao Paolo in 1974; Discipline and Punish published in 1975; the 1976 “Society must be defended” lectures; the 1979-1980 lectures on “the government of the living”; the 1979-1980 lectures on “subjectivity and truth”; the 1976 first volume History of Sexuality as well as subsequent volumes, ending in 1984. A full study is yet to be completed on the treatment of work by Foucault throughout his writings.

The impact made by Foucault’s writings can be observed throughout the social sciences that study work from specific angles: the history of work; the sociology of work; labour process theory; management and organisational studies; industrial relations; governmental studies; accounting and business, including business history. In all of these areas, Foucault’s writings continue to enrich and extend debates by adding a critical and historical depth to our understanding of the place of work in modern lives.

The wealth of empirical detail the work sciences gather on all aspects of contemporary work often has a critical edge itself. These details add new layers of complexity to the classical, negative accounts of modern work. The sheer weight of all these negative features of modern work leads one to ask: given all the “bads” of modern work, why should we try to justify the central place it has taken in our lives?

In the debates that focus more specifically on the centrality of work, Foucault’s writings matter in two ways especially: descriptively, in terms of the immense amount of historiographical detail his analyses of disciplinary and biopolitical power add to factual denunciations of modern work; and methodologically, for the decisive rejection he mounts of ahistorical approaches in the social sciences, about the treatment of work in particular.

The discipline of modern work

Without a doubt, of all of the books of Foucault, it is Discipline and Punish that has had the biggest influence on critical disciplinary accounts of modern work. Foucault’s famous descriptions of the rise of disciplinary society provide a sophisticated framework and themselves uncover a wealth of historical data, cementing the idea that the establishment of a capitalist economy coincides with new forms of coercion and oppression.

In the 1975 book, the new techniques of power that Foucault identifies as part of the deployment of discipline are applied as much to the experience of work as they are to the other fields, such as education, medicine or the military. Indeed, the fundamental logic underpinning the spread of disciplinary techniques across institutional realms is a historically novel one entirely, namely the “carceral”, a new obsession demonstrated by society to “confine” individuals in new ways, pursuing aims that are different from the confinement of the middle ages. The aim, precisely, is no longer to maintain the excluded outside or at the margins, but also to educate and to exploit them, and for that, to learn to know them better.

In his 1973-1974 lectures at the Collège de France on Psychiatric Power, Foucault applies this logic to work directly, for instance in focusing on the imposition of the “livret”, the employment record, on labourers:

in the [18th century], the great instrument of worker discipline, the employment document, the livret, is imposed on every worker. No worker can or has the right to move without a livret recording the name of his previous employer and the conditions under which and reasons why he left him; when he wants a new job or wants to live in a new town, he has to present his livret to his new boss and the municipality, the local authorities; it is the token, as it were, of all the disciplinary systems that bear down on him. (Psychiatric Power, 70)

In the lectures held a year before on “the punitive society”, the fundamental conceptual coupling of “surveilling and punishing” (the book’s title in French) was brought forward for the first time as the core functional nexus underpinning modern disciplines. In these lectures, the focus was even more explicitly the link between disciplines and capitalist exploitation. Work then was much more clearly central as an explanatory factor behind the rise of disciplines:

the supervision–punishment couple is imposed as an indispensable power relationship for fixing individuals to the production apparatus, for the formation of productive forces, and characterizes the society that may be called disciplinary. We have here a means of ethical and political coercion that is necessary for the body, time, life, and men to be integrated, in the form of labor, in the interplay of productive forces. (The Punitive Society, 196)

Reading these lectures of the years 1972-1974 as the preparatory material leading to Discipline and Punish thus further strengthens the descriptive force of all the passages in that book where the experience of work is shown to be wholly given over to the coercive, invasive, calculating control of disciplines. As the book famously outlines, new sciences, techniques and regulations, new architectural designs and modulations of time are constantly invented and refined to observe, train, control, shape, surveil and punish workers. The impression that arises from all these descriptions is that disciplinary power and all its different modes of exertion make the oppression of modern work a more intense, more intimate and exhaustive affair. To cite just one example, which describes a new procedure already mentioned in the lectures held three years before, Foucault analyses the emergence of the management and supervision functions as typical instances of disciplinary processes:

what was now needed was an intense, continuous supervision that ran right through the labour process (and that) also took into account the activity of the men, their skill, the way they set about their tasks, their promptness, their zeal, their behaviour… As the machinery of production became larger and more complex, as the number of workers and the division of labour increased, supervision became ever more necessary and more difficult. It became a special function, which had nevertheless to form an integral part of the production process, to run parallel to it throughout its entire length. A specialized personnel became indispensable, constantly present and distinct from the workers… But, although the workers preferred a framework of a guild type to this new regime of surveillance, the employers saw that it was indissociable from the system of industrial production, private property and profit… Surveillance thus becomes a decisive economic operator both as an internal part of the production machinery and as a specific mechanism in the disciplinary power. (Discipline and Punish, 174)

If modern work has become intrusive and oppressive in all these new kinds of ways, if the experience of work is now thoroughly framed by the attempt to intensify exploitation, then advocating its centrality would seem rather short-sighted and ill-advised.

A Foucauldian version of the social factory

Beyond the empirical features of oppressive modern work institutions, Foucault also presents his own version of what operaists in Italy a decade earlier started to describe as the “social factory”, that is, the attempt by capitalism to refashion subjectivities and social relations to make them entirely adjusted to the functional requirements of economic activity. This means, precisely, making work the central, guiding principle in every social realm (notably the family and education), and for every person in how she conceives of her life goals and values. In this case, the centrality of work is not just imposed through external, institutional measures and techniques, it is itself the central ideological mechanism that modern capitalist society works at establishing.

We noted at the outset that Foucault had shown interest in the work ethos arising with the shift from “classical” to disciplinary society already in the History of Madness. Another text in which the Foucauldian version of the social factory and the new work ethic is clearly presented is the series of five lectures he held in Sao Paolo in 1975, exactly at the time when he was beginning to complement the disciplinary hypothesis with the biopolitical one.

Pursuing the underlying Marxian strand of his analyses at the time, Foucault gave a new disciplinary twist to the core idea that exploitation and the extraction of surplus-value rely on workers being shortchanged in relation to the time they put into production. Modern capitalism, he argues in 1975, works through a disciplining of people’s times, seeking to make every moment of workers’ time functionally useful to production:

the modern society that formed at the beginning of the nineteenth century was basically indifferent or relatively indifferent to individuals’ spatial ties: it was not interested in the spatial control of individuals insofar as they belonged to an estate, a locale, but only insofar as it needed people to place their time at its disposal. People’s time had to be offered to the production apparatus; the production apparatus had to be able to use people’s living time, their time of existence. The control was exerted for that reason and in that form. Two things were necessary for industrial society to take shape. First, individuals’ time must be put on the market, offered to those wishing to buy it, and buy it in exchange for a wage; and, second, their time must be transformed into labor time. That is why we find the problem of, and the techniques of, maximum extraction of time in a whole series of institutions. (“Truth and Juridical Forms”, 80)

A whole set of new social policies and institutional procedures, some of which seemingly remote from the world of production and apparently serving welfare ends, were put in place to make the whole of workers’ time functionally welded to capitalist interests:

During the nineteenth century, a series of measures aimed at eliminating holidays and reducing time off were to be adopted. A very subtle technique for controlling the workers’ savings was perfected in the course of the century. On the one hand, in order for the market economy to have the necessary flexibility, the employers must be able to lay off workers when the circumstances required it; but, on the other hand, in order for the workers to be able to start working again after an obligatory period of unemployment, without dying of hunger in the interval, it was necessary for them to have reserves and savings— hence the rise in wages that we clearly see begin in England in the 1840s and in France in the 1850s. But when the workers had money, they were not to spend their savings before their time of unemployment came around. They mustn’t use their savings whenever they wished, for staging a strike or having a good time— thus the need to control the worker’s savings became apparent. Hence the creation, in the 1820s and especially the 1840s and 1850s, of savings banks and relief funds, which made it possible to channel workers’ savings and control how they were used. In this way, the worker’s time— not just the time of his working day but his whole lifespan— could actually be used in the best way by the production apparatus. Thus, in the form of institutions apparently created for protection and security, a mechanism was established by means of which the entire time of human existence was put at the disposal of the labor market and the demands of labor. This extraction of the whole quantity of time was the first function of these institutions of subjugation. It would also be possible to show how this general control of time was exercised in the developed countries by the mechanism of consumption and advertising. (“Truth and Juridical Forms”, 81)

Radical historicism

One important generalising conclusion Foucault draws from these institutional analyses, is that disciplinary and emerging biopolitical techniques therefore aimed at creating a new injunction to work. A whole set of new mechanisms sought implicitly and indeed often explicitly to instill the urge to work, in other words, to establish the centrality of work not just in social structures, but even psychologically:

Someone said that man’s concrete essence is labor. Actually, this idea was put forward by several people. We find it in Hegel, in the post-Hegelians, and also in Marx, the Marx of a certain period, as Althusser would say. Since I’m interested not in authors but in the function of statements, it makes little difference who said it or exactly when it was said. What I would like to show is that, in point of fact, labor is absolutely not man’s concrete essence or man’s existence in its concrete form. In order for men to be brought into labor, tied to labor, an operation is necessary, or a complex series of operations, by which men are effectively—not analytically but synthetically— bound to the production apparatus for which they labor. It takes this operation, or this synthesis effected by a political power, for man’s essence to appear as being labor. So I don’t think we can simply accept the traditional Marxist analysis, which assumes that, labor being man’s concrete essence, the capitalist system is what transforms that labor into profit, into hyperprofit [sur-profit] or surplus value. The fact is, capitalism penetrates much more deeply into our existence. That system, as it was established in the nineteenth century, was obliged to elaborate a set of political techniques, techniques of power, by which man was tied to something like labor— a set of techniques by which people’s bodies and their time would become labor power and labor time so as to be effectively used and thereby transformed into hyperprofit. But in order for there to be hyperprofit, there had to be an infrapower [sous-pouvoir]. A web of microscopic, capillary political power had to be established at the level of man’s very existence, attaching men to the production apparatus, while making them into agents of production, into workers. This binding of man to labor was synthetic, political; it was a linkage brought about by power. There is no hyperprofit without an infrapower. (“Truth and Juridical Forms”, 86)

From this historical hypothesis, a major methodological consequence derives: namely, that it is intrinsically misguided to argue about work and its value for individuals and society in transhistorical terms, as if there was an essence of the human for which work attributes would somehow matter analytically. Work is indeed central to individuals and society, but not “analytically”: it has been made central, through deliberate and not so deliberate disciplinary and biopolitical strategies, for the purpose of control and exploitation. Historiographically-based, genealogical analysis leads to a radically historicist take on work issues, which condemns as illegitimate armchair or essentialist arguments about work.

COVID-19 and a new panopticon?

Over the past several decades, as we noted earlier, Foucault’s writings have made a significant contribution to understanding the centrality of work in our lives. Today this impact persists, with scholars in many areas continuing to look to Foucault to find valuable tools which they can use to address contemporary problems surrounding the inescapable centrality of work. Organisational theory has been a major hub for such scholars, but perhaps the area of most impact has been on the discipline of Surveillance Studies.

Foucault’s ongoing significance is even more obvious today in the changing context of work caused by Covid-19. With the pandemic making a resurgence around the world, the vision to which Foucault gave so much analytical depth and historiographical detail, of modern forms of power exerting themselves through distant control and surveillance mechanisms is gaining traction once again.

The ultimate impact of Coronavirus on work is not yet determined, and it will not be for some time. Yet some consequences can already be seen. At least for those who remain in work, the most obvious impact has been where work takes place. Working from home, a technologically enabled phenomenon which has been on the increase for some time, has become a necessity for many. Due to lower building costs, lower worker enthusiasm for commuting, and indeed lower environmental pressure, this is a phenomenon that may well be around to a significant degree well after this pandemic. Working from home, ‘telework’, allows workers greater freedom, and, on the other side of the scales, it seems to allow employers less control. This lack of control is a concern for many businesses, as is noted, for instance, in this recent OECD policy report:

“[T]o the extent that control over workers is exerted through face-to-face interactions and physical presence, telework can hinder managerial oversight and aggravate principal-agent problems, e.g. ‘shirking’ … Telework requires a change from assessing performance in terms of inputs, i.e. time worked, to outputs, which implies giving up some control over workers and, in principle, provides workers with more opportunities to “slack”. However, digitalisation may also lead to more data on worker performance becoming available to managers, which may ultimately provide more information for efficient monitoring of workers than is generally available in a traditional office environment.”

More people working from home means that employers are giving up “some control over workers”. Technology, however, allows surveillance and monitoring to be effected at a distance, entering to the heart of the home from any remote distance and allowing companies to mitigate against their ‘loss’. Worker surveillance is not, of course, a managerial tool that has become available just with the birth of the internet or because of this pandemic. It came into prominence with modernity and the very first steps of industrialisation. As Foucault demonstrates for us, focusing on these steps allows us to better understand the destination we find ourselves at today. We recall the many passages of Discipline and Punish, for instance, that seemed to foretell the ubiquity of panopticon-techniques:

The gradual extension of the wage-earning class brought with it a more detailed partitioning of time 'If workers arrive later than a quarter of an hour after the ringing of the bell . . .' (Amboise); 'if any one of the companions is asked for during work and loses more than five minutes . . .', 'anyone who is not at his work at the correct time . . .’. But an attempt is also made to assure the quality of the time used: constant supervision, the pressure of supervisors, the elimination of anything that might disturb or distract; it is a question of constituting a totally useful time: 'It is expressly forbidden during work to amuse one's companions by gestures or in any other way, to play at any game whatsoever, to eat, to sleep, to tell stories and comedies'; and even during the meal-break,' there will be no telling of stories, adventures or other such talk that distracts the workers from their work … Time measured and paid must also be a time without impurities or defects; a time of good quality, throughout which the body is constantly applied to its exercise. Precision and application are, with regularity, the fundamental virtues of disciplinary time. (Discipline and Punish, 150)

It may be the case that even with the latest technological improvements, notably with tracking and intrusive forms of tele-surveillance, not all workers can be monitored to the same degree as in traditional environments where they were physically under the gaze of managers. For this reason some business theorists are calling for an end to traditional salaried work, instead suggesting that employees who work from home should have their pay linked with their outputs. However, for the workers themselves the actual technological limits of managerial surveillance may not matter. The significance of technology, particularly technological reach, is entirely minimal when compared to the internalised effects of that technology by workers. In other words, it may simply be irrelevant that technology itself cannot keep up with worker freedom if indeed the “panopticon effect” continues to exert its influence:

A real subjection is born mechanically from a fictitious relation. So it is not necessary to use force to constrain the convict to good behaviour, the madman to calm, the worker to work, the schoolboy to application, the patient to the observation of the regulations. (Discipline and Punish, 202).

A Foucauldian perspective on the subject at work

Yet, although managerial oversight might escalate in ways that are increasingly internalised, this story is not one sided. Critical management studies have been exploring at length the avenue opened up by Foucault’s famous saying that:

where is power, there is resistance to power (History of Sexuality, vol.1, 95)

Resistance at and against work is a major topic of inquiry in critical management and organisation studies. Indeed, in a much-quoted passage of a 1982 interview, Foucault made resistance prior to power in the constitutive tension linking power and resistance. This move echoed again an operaist idea, namely that capitalism changes in its structures and class composition in response to challenges from the working class:

If there is no resistance, there would be no power relations… So resistance comes first, and remains superior to the forces of the process; power relations are obliged to change with the resistance. So I think that resistance is the main word, the keyword, in this dynamic (“Sex, Power and the Politics of Identity”, 167).

Furthermore, as is well-known, in his late work, Foucault started to refocus his historical analyses to the subject as site of resistance and agent of truth-seeking. In the 1978-1979 lectures on “the birth of biopolitics”, he seems to embrace the new economic philosophy of neoliberalism precisely for that reason. In a passage in which he takes to task both classical political economy and its critique by Marx and Keynes, he explicitly emphasises the need to turn economic analysis to the level of the subject herself, as the agent of activity:

This means undertaking the economic analysis of labor. What does bringing labor back into economic analysis mean? It does not mean knowing where labor is situated between, let’s say, capital and production. The problem of bringing labor back into the field of economic analysis is not one of asking about the price of labor, or what it produces technically, or what is the value added by labor. The fundamental, essential problem, anyway the first problem which arises when one wants to analyze labor in economic terms, is how the person who works uses the means available to him. That is to say, to bring labor into the field of economic analysis, we must put ourselves in the position of the person who works; we will have to study work as economic conduct practiced, implemented, rationalized, and calculated by the person who works. What does working mean for the person who works? What system of choice and rationality does the activity of work conform to? As a result, on the basis of this grid which projects a principle of strategic rationality on the activity of work, we will be able to see in what respects and how the qualitative differences of work may have an economic type of effect. So we adopt the point of view of the worker and, for the first time, ensure that the worker is not present in the economic analysis as an object—the object of supply and demand in the form of labor power—but as an active economic subject. (Birth of Biopolitics, 223).

Applied to the critique of discipline and surveillance in the workplace, his late emphasis on the primacy of resistance and the subjective standpoing opens the door to a different Foucauldian take on work, one that no longer so obviously bolsters arguments against its centrality. For this late emphasis on the subject as a site of resistance and indeed as a potential driver of change invites us to look carefully, at a similar level of detail as Foucault’s analyses are a model of, at the concrete actions that individual workers and worker collectives undertake in order to resist surveillance, disciplining and exploitation. Once this door is open, it might be the case that an important source of motivation for worker resistance and organising in fact are precisely the goods that worker expect from –and maybe sometimes find in– their work. Depending on what we then find behind this door of resistance to power, asking “what working means for the person who works” could in fact lead us to reassert something like the great significance, some kind of “centrality”, of work.

As always, suggestions and contributions are welcome to continue to enrich the repository.

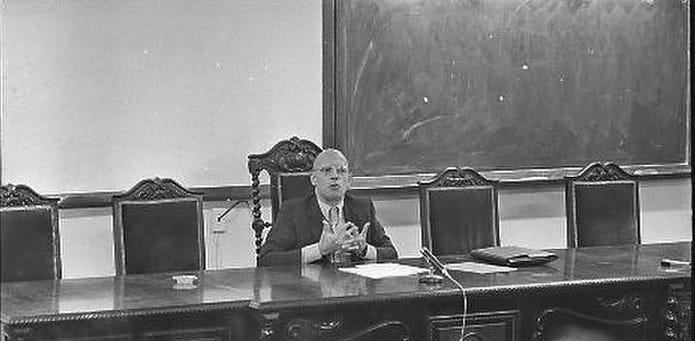

Image

Michel Foucault during a series of conferences in Rio de Janeiro (30 October 1974), Brazilian National Archives.