'Giving back to the commons': contemporary readings of Locke's theory of work

(by Thomas Corbin)

The previous newsletter looked at the place of work in the thought of Thomas Hobbes. Hobbes it seemed, did have some interesting things to say about work, particularly in relation to the duties of the sovereign. However, amongst the writers in the early modern cannon who wrote the most influentially on work, it is not Hobbes but rather John Locke who takes the title.

Locke discussed work throughout his life and wrote some very interesting (and rather under-explored) things about workers in his early economic writings (Hundert 1972, p.5). However, it was not until his Second Treatise (1689) that Locke put forward what was to become his greatest contribution to the study of labour, production, and property:

“In the early economic writings Locke, like the majority of his contemporaries, was concerned with the role of the worker and only tangentially interested in the nature of work itself. The Second Treatise of Government, however, was the first modern piece of major significance which, whatever its other purposes, considered the relationship between man, his property, environment, and society in terms of the nature and value of human labor; and in his discussion of property relations Locke established the foundations for the modern conception of labor.” (Hundert 1972, p.7)

Locke puts this foundation forward in the fifth chapter of his Second Treatise titled ‘Of Property’. There is much in this chapter which is of interest, but the part with the most ongoing importance in the history of ideas is §27:

“Though the Earth, and all inferior Creatures be common to all Men, yet every Man has a Property in his own Person. This nobody has any Right to but himself. The Labour of his Body, and the Work of his Hands, we may say, are properly his. Whatsoever then he removes out of the State that Nature hath provided, and left it in, he hath mixed his Labour with, and joyned to it something that is his own, and thereby makes it his Property. It being by him removed from the common state Nature placed it in, hath by this labour something annexed to it, that excludes the common right of other Men. For this Labour being the unquestionable Property of the Labourer, no man but he can have a right to what that is once joyned to, at least where there is enough, and as good left in common for others.” (Second Treatise, p.287)

The essence of this theory is that property is that material which results from one’s own labour. Understandably, this theory of property has been taken by many to imply - even simply state - a ‘labour theory of value’ (Vaughn 1978, p.313). Since land and other natural elements in isolation are relatively worthless to people, it is labour that provides value. Indeed, it could be said that such element has value only in the potential sense that in the future it might be combined with labour. As Locke writes:

“[F]or it is labour indeed that puts the difference of value on everything; and let any one consider what the difference is between an acre of land planted with tobacco or sugar, sown with wheat or barley, and an acre of the same land lying in common, without any husbandry upon it, and he will find, that the improvement of labour makes the far greater part of the value.” (Second Treatise, p.296)

The significance of this realisation, this connection between labour and value, is a key reason why Marx thought, as in this preparatory note to Capital, that Locke’s writings “served as the basis for all the ideas of the whole of subsequent English political economy”. Political economy is of course a key frame of analysis for the argument we see here, yet there are many ways that Locke’s writings both can and have been explored, critiqued, and built upon. Perhaps the most common of those exegetical frameworks over time has been to read the famous passage in purely economic, rather than political economic, terms. More recent scholarship, however, has attempted to broaden the frame. At the core of Locke’s writings on work, some argue, we see not an economic concern but a moral one:

“In their assault on Locke’s labor theory of value, philosophers construe Locke’s concept of labor in purely physical terms and they construe his concept of value in purely economic terms, but these are not Locke’s concepts of labor or value. His concept of labor refers to production, which has intellectual as well as physical characteristics, and his concept of value serves his moral ideal of human flourishing, which is a conception of the good that is more robust than merely physical status or economic wealth.” (Mossoff 2012, p.3)

This concern for ‘human flourishing’ suggests that Locke’s theory of work is even more relevant to today’s discussions on work than was traditionally understood. Although, it is not yet clear in exactly what sense the connection between labour and value actually allows or encourages such a concern. Many options present themselves of course. We might, for example, bring Locke to debates on ‘meaningful work’. But for Locke himself it seems we may need to move our analysis further into a specifically political understanding:

“For Locke, labor is a directive principle. It is what enables us to meet our needs by giving the right kind of direction to materials that do not supply that direction for themselves. As such, the contribution of labor - of creativity and direction - to the resources we produce is unique, and different in kind from the contribution that materials make. The point is not allocations, rewards, or exoneration. The point is to find a way to live together. The demand for a directive principle is a reality of the world in which we must find a way to survive. And the difference between prosperity and destitution in our world, Locke finds, is the direction our labor gives our world.” (Russell 2004, p.318)

This alternative portrait of Locke’s theory of work as focused on a notion of ‘human flourishing’, with individual work efforts the basis for a community in which we ‘find a way to live together’, positions him closely to many of today’s theories of work. Such a theory fits remarkably comfortably with the emerging philosophy of work literature which sees ‘work’ itself as a far broader enterprise than one focused simply on financial concerns.

One way we might dig deeper into this relationship is by briefly exploring Locke’s discussion on ‘waste’.

In putting Locke’s theory of work to work in a modern context, one particularly productive area has been environmental sustainability. Although in general his understanding of property and in particular his discussions of working natural goods suggests a ‘taking’ from nature contrary to what today we may think of as sustainable, Locke actually seems to anticipate such a concern and may have built morally based preventative measures into his account of work as a result:

“It will perhaps be objected to this [theory of property], that if gathering the acorns, or other fruits of the earth, &c. makes a right to them, then any one may ingross as much as he will. To which I answer, Not so. The same law of nature, that does by this means give us property, does also bound that property too. God has given us all things richly, 1 Tim. vi. 12. is the voice of reason confirmed by inspiration. But how far has he given it us? To enjoy. As much as any one can make use of to any advantage of life before it spoils, so much he may by his labour fix a property in: whatever is beyond this, is more than his share, and belongs to others. Nothing was made by God for man to spoil or destroy.” (Second Treatise, p.290)

There are two clear points of significance here. First, in the same way as Locke argues for his account of property he also argues for a limit to property. This limit brings Locke’s discussion into conversation with contemporary scholarship on work, such as we recently discussed under the theme of degrowth. The second point of significance is the nature of that limit itself, which Locke bases on waste:

“Locke's "labor" is not recreation, it is not purposeless action, and, most important, it is never an action that destroys or wastes goods.” (Mossoff 2002, p.16)

This is a fascinating vision of what has typically been seen as a classical economic theory. It is also a vision which drastically extends the potential application of Locke’s theory:

[A]gainst those who claim that property rights regimes damage the commons, Locke claims that proprietized labor, in fact, gives back to the commons, and results in an increase to it; hence, "he who appropriates land to himself by his labor, does not lessen but increase the common stock of mankind" (II, 37). In contemporary terms, property regimes have positive externalities.” (Hull 2009, p.69)

From a theory of work focused merely on economic understandings of private property to a political account of work aimed at human flourishing in harmony with environmental sustainability. It seems that perhaps Locke’s theory of work really is far more than just a stepping-stone in the history of ideas properly suited only for a 17th century audience.

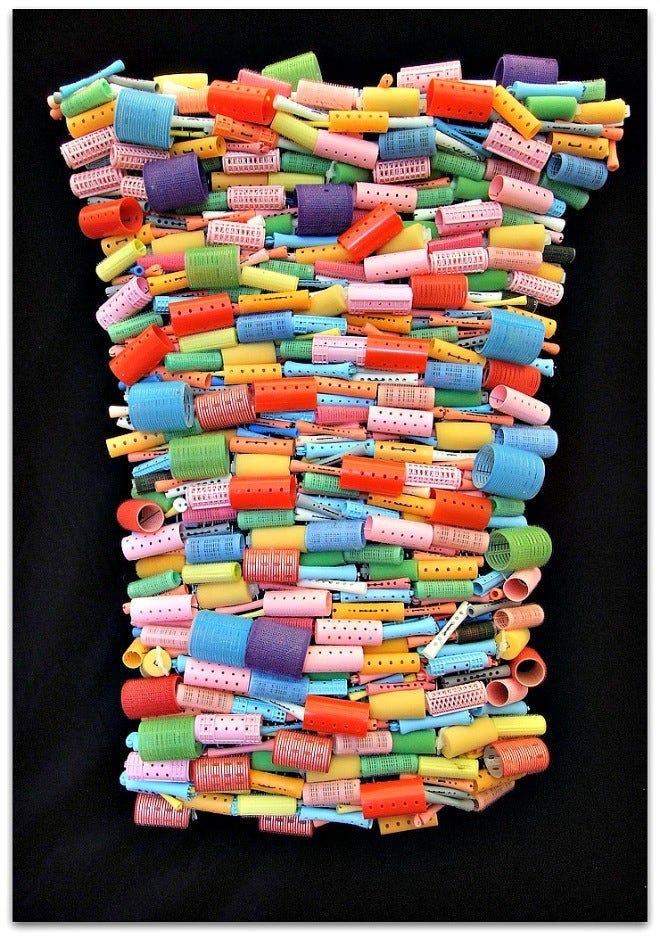

Image

Ellen Morisette, “Beauty School Dropout”, c.2004-2008.